SUMMER 2025

Drive-Through Mary

Her mother was a beloved piano teacher. But in her later years, she started listening to a different kind of music.

- Story by Alexandra M. Stewart

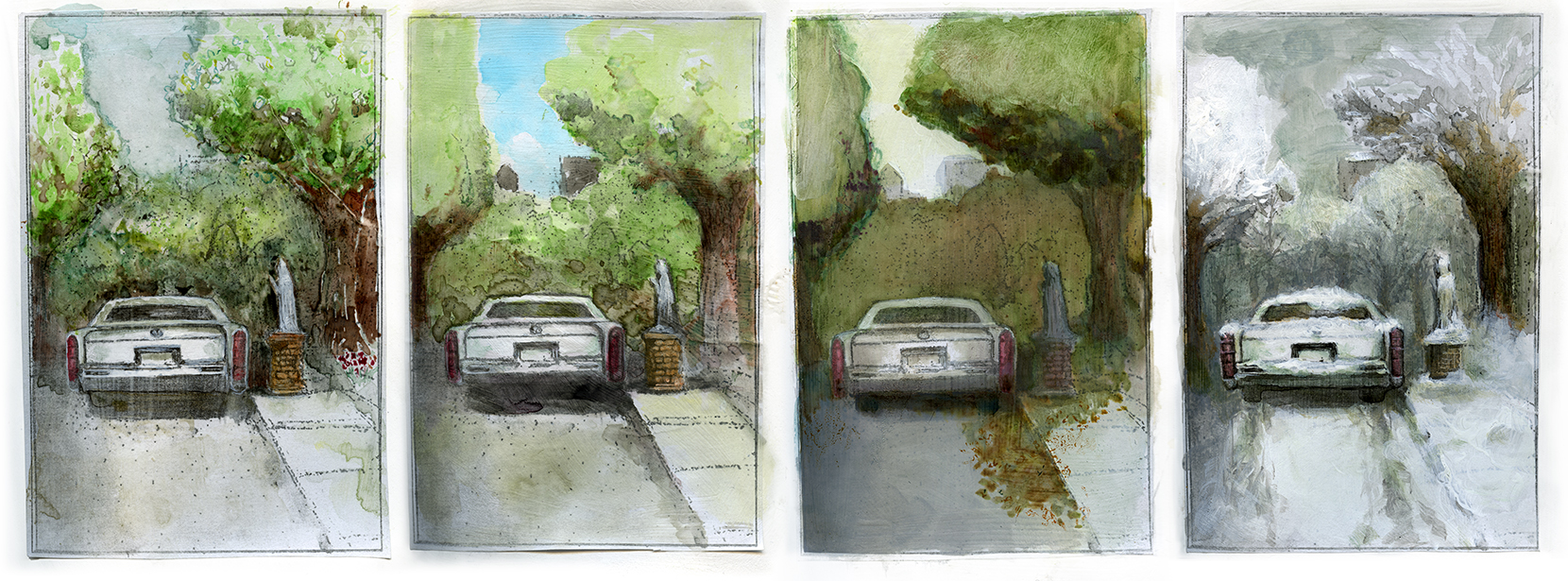

Illustrations by Sacha Moo

WHEN I DREAM about the town I grew up in, I sometimes am walking by St. Mary School, a practical, single-story 1950s building across the street from its impressive, brick-and-stained-glass church. Many of my classmates went to St. Mary, and around the age of eight, when they were preparing for First Communion, I asked my mother if we were religious. Since we didn’t go to that church, I figured we weren’t Catholic, and I knew we weren’t Jewish. (I thought the difference between bar and bat mitzvah was a typo.) But I didn’t know what other options there were. When I asked her, my mother was standing in her bathroom, getting ready for work, wearing pants and a bra, curlers in her hair, and she froze with the mascara wand in her hand. Normally, if I attempted conversation with my mother while she was getting dressed, she kept moving and answered me absently. But now she studied my face, three horizontal lines appearing on her forehead, as they did when she was focused. I was never afraid of my mother, but in that moment the intensity of her attention frightened me. She asked, “Who wants to know?” I stuttered a response, avoiding eye contact. “No one, I guess.” But I didn’t know what to say when the girls at school asked me about my own First Communion, and I was hoping for some guidance. “I suppose I just want to know.”

Up to that point, we had gone as a family to the Ukrainian Orthodox churches in Manhattan and Staten Island, near where my mother’s friends lived. We had really only gone a few times, for holidays and funerals. I mostly associated those experiences with discomfort (hard pews and itchy tights), embarrassment for not understanding the service (it was in Old Slavonic), and my mother’s palpable relief when the service ended. After an early and unhealthy marriage, my mother had largely broken with the Ukrainian church as part and parcel of breaking with the community she felt oppressed by. Standing in the bathroom, I squirmed and glanced at my mother. She was looking sternly in the mirror. After some thought, she finally said, “If anybody asks you, you tell them we’re not religious, but we’re very, very spiritual.”

What did that mean to my mother? We lived in a wealthy, moderately conservative town, within commuting distance from New York City, where both my parents worked and where the Ukrainian ex-pat community was rooted. They had chosen the town for its excellent schools, despite the cartoonish snobbery of the residents and the high cost of living. The period of my friends’ Communions was the most affluent of my parents’ life, and my mother, as a first-generation immigrant who had lived in poverty as a child, understood the precarity of wealth and the challenge of walking the fine and wobbly tightrope of fitting in.

In this white, upper-middle-class suburb, my mother gave off a whiff of the Old World combined with the perfume of the New Age. The oriental rugs and walls of bookshelves in our home sparkled with healing crystals and icons of various religions. My mother was drawn to powerful women, and so small wooden and gold-leaf paintings of Mary sat next to metal figurines of the goddess Guanyin, the Buddhist embodiment of compassion. She consulted, in no particular order, a psychic friend in Hawaii; Christiane Northrup, the OBGYN who wrote Women’s Bodies, Women’s Wisdom; and her group of Ukrainian girlfriends who called themselves The Thursday Lunch Club. She had trained to be a concert pianist, but sexism and having children (as she told me and my sister, quite directly) made a career as a performer almost impossible. But above all, she became an admired and beloved teacher, giving piano lessons both from our home in Connecticut and her studio in Carnegie Hall.

Her students ranged from the remarkable, such as Gwan-Ying Wu, who became a classical superstar in Taiwan in the 1980s, to the bread-and-butter, like the No-Brothers, a pair of athletes (and our classmates) whose parents wanted them to be well-rounded. The most frequent word my sister and I overheard during their lessons was “No!” when my mother corrected their mistakes and made them start a measure over. Almost two decades later, the younger of the No-Brothers told me he still treasured a figurine of a lion that my mother had given him, to remind him of his strength. It was this bottomless generosity, even when her patience was spent, for which my mother was venerated.

OUR FAMILY HAD no particular attachment to St. Mary. Some of our classmates went to Mass at the church. I was in it once or twice. When my sister and I were little, our mother attended aerobics classes at the school-turned-community-center and would drop us off at the babysitting room while she and other mothers did modified Jane Fonda workouts in the cafeteria/gym/auditorium. At age fifteen, I took driver’s ed classes there, one evening a week after school, with a boy I liked. The most exciting ten minutes were between the end of class and when our parents picked us up. This boy and I would wait outside in the spring twilight, near the concrete sculpture of Mary that faced the parking lot, and talk about nothing that I remember today, but everything then seemed charged with meaning.

By then, my parents were divorced, and my mother was already seven years past her first breast cancer diagnosis. I was nervous about driving, but she couldn’t wait for me to have my license so that I could help her—drive myself and my sister to high school, return a video to Blockbuster, pick up a gallon of milk. She needed the help. As much, she needed some downtime, and when I gradually grew bold enough to take my sister to Taco Bell using spare change we found around the house, she was thrilled. She was glad for a break from the relentless parenting of two teenagers, but it also assuaged her guilt and worry that her illness was making us grow up too fast.

Other than in The Thursday Lunch Club, my mother didn’t confide in many people. This is not to say she didn’t tell people about her life. She would share her latest diagnosis or most recent challenge (car trouble, unexpectedly large utility bill, needed household repair) with the parents of her students, with cashiers at the grocery store, or with nurses who inserted her IV.

She created a narrative in those days of herself as “a single, working mother, just trying to spend time with her two teenage daughters.” She once got out of a speeding ticket this way.

But my mother’s story was grander, more tragic. She famously learned to play the piano by using a drawing of a keyboard that my grandfather made on a piece of cardboard fished out of a dumpster. Later, she harnessed her talent with tooth-gritting determination and attended Juilliard and Yale. As an immigrant child in a New York public school, she was forced to take an IQ test. Her score was so high, and the prejudice against immigrants so strong, that the teacher concluded the test had been misscored. She had my mother take it again. The score the second time was one point higher. Although as a child she knew the feeling of acute hunger—when her family shared one head of cauliflower for dinner—in her mid-life, my mother owned four Steinway baby grand pianos. The first in her family to be diagnosed with breast cancer, she buried first her mother, then her younger sister. It was easy to admire and romanticize the challenges my mother had faced, and, viewed from a distance, hers was the classic American immigrant story: fled war, arrived in the US, experienced poverty and hunger, worked hard, achieved much, had talent rewarded, lived in a large house, made sure her children never experienced the privations she did. Her childhood trauma, her two marriages (the more lasting one to my father), the grief of losing so much of her family (grandparents, parents, and sister), and the unending challenge of getting through each day—each layer became a heavier weight on my mother’s soul. She confided in me about family feuds, hurt feelings, her interpretations of my father’s calmly pragmatic choices. These became stones for me to carry, like the beach stones she collected for the path she planned to make one day in our yard.

Before she started her round of piano lessons for the evening, my mother would rest in her bed. She held court there like a sphinx, using the bedside table as her mission control, her tools and weapons close at hand: phone and answering machine, datebook, mug of cold coffee, stack of unopened bills, The Mists of Avalon and People magazine, and a fistful of colored pens. In her bathrobe with her make-up on, she just needed a moment to put on one of her silk blouses the color of tropical flowers and the earrings like small chandeliers. She would smooth the worry off her forehead, put on her public voice, and spritz herself with the perfume that smelled like mangos.

But for a few precious minutes before the students showed up, my sister and I had her to ourselves, wrinkles, worries, and all.

In one of those windows of time back then, my mother and I sat next to each other in her bed, watching a black-and-white movie. (She who pooh-poohed romance and fairy tales made sure I watched Casablanca, When Harry Met Sally, Love Story, and An Affair to Remember.)

“You know that sculpture of Mary in front of the school?” she said to me.

I paused. “St. Mary School?”

She confirmed. I glanced at my mother and waited.

“Sometimes I go there,” she said.

“To the statue?”

“Yes.” She wasn’t looking at me. She continued to look at the screen.“When it’s too much or things are too hard, I park in front of the statue, and I talk to her.”

“You pray?” I found this hard to imagine.

She considered. “It’s not praying, really. It’s more like a conversation.”

“What does she say?”

My mother answered obliquely. “Well, she knows sorrow, you know.”

I couldn’t argue that. “Does it help?” I asked. My god, anything that could help. The crystals, the psychic, the lunches, the chemo, the old movies. Anything that could help my mother was fine by me.

She nodded. Her chin had a dimple in the middle, and it was pointed up, a little gesture of defiance. Our attention returned ostensibly to the movie, and we fell silent. After a few moments, my mother said, “I call her the Drive-Through Mary.”

Of course these conversation-prayers didn’t save my mother. Neither did the self-help books, the meditation, or the macrobiotic diet. She still died of breast cancer metastasized to other organs: her lungs, her liver, eventually her brain. After she died, her students, her friends, her family—we were all guilty of it—we lionized her, canonized her, and valorized her struggles, which felt almost Biblical. “God never gives you more than you can handle,” she liked to say to people. “I just wish He didn’t trust me so much.”

How many of us repeat the things she said, the punchlines, the words of advice? How have they steered our lives and shaped our choices? As her daughter, I saw her dark days and saw her gnawed by regret. When my sister and I were faced with the difficult task of writing her obituary, we did our best to capture our mother, the teacher and concert pianist. Privately, when we now reflect on our mother’s choices, we often conclude that we should do something different. We should not be so accommodating, so selfless, such a martyr. Nonetheless, her voice guides me throughout the day, when I get dressed in the morning (“You should wear blazers more.”), when I have a conflict with a colleague (“Be generous. You don’t know what she’s going through.”), and when my sister calls (“She needs to know we love her unconditionally.”). My mother died twenty years ago, and, yet, how many of us still ask ourselves, in moments of decision,“What would Maria do?”