Alumni

Portland Magazine

June 19, 2019

The Story of a Young Pilot

by Eileen Bjorkman

THE LINGERING SUMMER sunlight made it easy to find the sculpture—the robed hands clasped in prayer, the shock of white against a backdrop of red bricks. Carol Leitschuh had learned about the Praying Hands Memorial just minutes earlier that evening in 2016, from a priest at dinner. Now, as she drew closer to the sculpture, she began to see names engraved in some of the bricks, memorializing students from University of Portland who died serving their country during World War II. Carol had come to find one name: her uncle, John H. Carroll Jr., whom she had never met.

THE LINGERING SUMMER sunlight made it easy to find the sculpture—the robed hands clasped in prayer, the shock of white against a backdrop of red bricks. Carol Leitschuh had learned about the Praying Hands Memorial just minutes earlier that evening in 2016, from a priest at dinner. Now, as she drew closer to the sculpture, she began to see names engraved in some of the bricks, memorializing students from University of Portland who died serving their country during World War II. Carol had come to find one name: her uncle, John H. Carroll Jr., whom she had never met.

A few days later, Carol showed photos of the memorial to her aunt Jeanne, John’s younger sister. Jeanne stared at the photo of the brick inscribed with the name of her only brother, who had died 72 years earlier. The University’s Class of 1948 had built the memorial, but somehow its existence had escaped her and the rest of the Carroll family. Her voice tinged with sadness, she said, “That’s the only marker we have for John.”

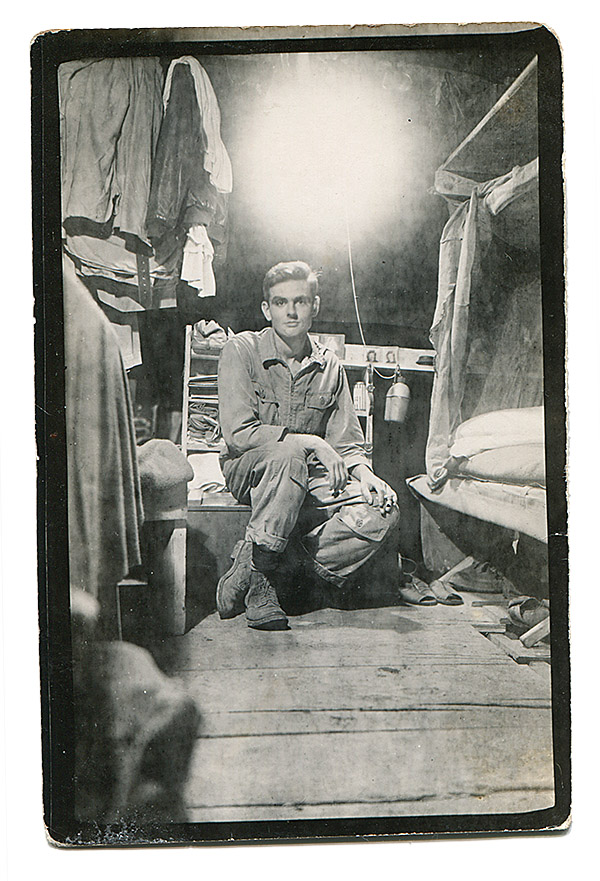

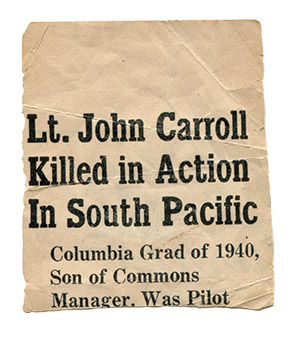

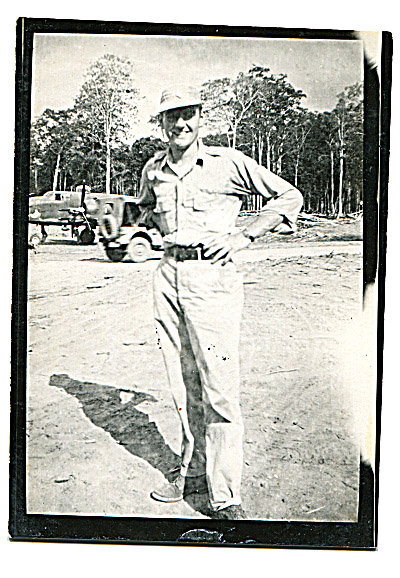

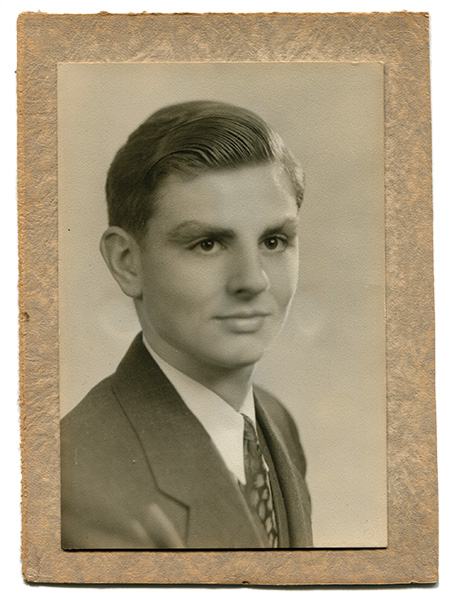

Born on May 5, 1922, John H. Carroll Jr. seemed destined to become a renaissance man: during high school, he lettered in football, was president of his sophomore class, and was a member of the physics, chemistry, and drama clubs. He learned to ski without a chairlift, climbing to the top of a mountain in the Cascades and then skiing down. After graduating from high school in 1940, he began studying for an engineering degree at University of Portland, where his father, John H. Carroll Sr., worked as a purchasing agent. The next year, John attended a civil pilot training course in Portland, entering a pool of pilot candidates the military could call upon if needed. The senior Carroll had received a Purple Heart in World War I and was reluctant to let his only son enlist in the military, but after the attack on Pearl Harbor, he gave his blessing. John hated the war but wanted to serve and fulfill what he considered his duty to help keep America safe. He left school to enter the Army Air Force in March 1942 and received his commission and Air Force pilot wings on January 7, 1944. He returned to Portland to marry Violet Law five days later and then left for the South Pacific, where he flew B-25 bombers.

Born on May 5, 1922, John H. Carroll Jr. seemed destined to become a renaissance man: during high school, he lettered in football, was president of his sophomore class, and was a member of the physics, chemistry, and drama clubs. He learned to ski without a chairlift, climbing to the top of a mountain in the Cascades and then skiing down. After graduating from high school in 1940, he began studying for an engineering degree at University of Portland, where his father, John H. Carroll Sr., worked as a purchasing agent. The next year, John attended a civil pilot training course in Portland, entering a pool of pilot candidates the military could call upon if needed. The senior Carroll had received a Purple Heart in World War I and was reluctant to let his only son enlist in the military, but after the attack on Pearl Harbor, he gave his blessing. John hated the war but wanted to serve and fulfill what he considered his duty to help keep America safe. He left school to enter the Army Air Force in March 1942 and received his commission and Air Force pilot wings on January 7, 1944. He returned to Portland to marry Violet Law five days later and then left for the South Pacific, where he flew B-25 bombers.

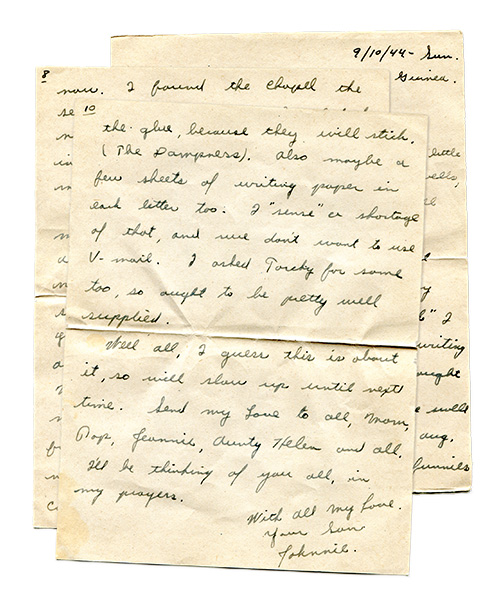

John wrote regular letters home to Violet and his parents. He told his parents he attended Catholic Mass and Adoration regularly; he found great comfort in the rites. He looked forward to having the war behind him. He ended each letter: “Sending lots of love, Your son, Johnnie.”

On November 12, 1944, John’s B-25 was hit by Japanese anti-aircraft artillery during a raid in the the Dutch East Indies (now Pegun Island). One of the other pilots in the formation saw the back part of John’s bomber engulfed in flames. The nose of the crippled aircraft pitched up, and the plane stalled, spun into the ground, and exploded. The aircraft had been flying too low and too fast for the five crewmembers to have any chance of bailing out. An Army Catholic priest went to the site of the crash the next day and celebrated Mass.

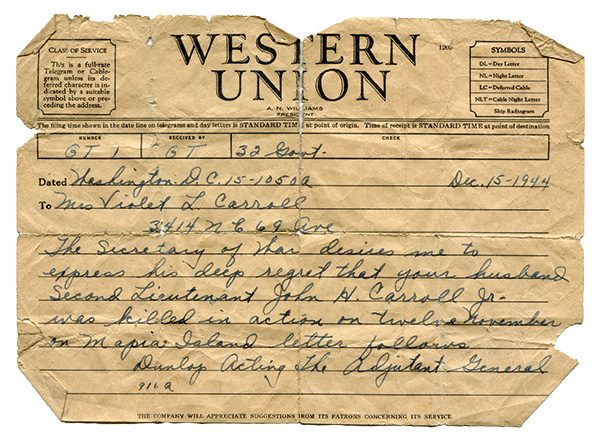

The Army was slow to notify the Carroll family of John’s death. He wrote his last letter home two weeks before he died, and his parents and wife struggled to understand why they suddenly stopped hearing from him. Then one day Violet received a shipment containing his belongings, although the Army still hadn’t confirmed or denied his death. She finally received a telegram with the official notification on December 15, 1944.

John’s body was not recovered. For his service, he received the Purple Heart and the Air Medal. The family’s deep faith and a letter from the priest who performed the Mass provided comfort: he assured the family that no one was better prepared to meet God than John.

After the war ended, the military tried to identify as many remains as they could. The success rate was low, given technology at the time. Sergeant Charles Langord was the only one identified from the five crewmembers aboard John’s B-25. A letter to Violet in 1950 expressed sympathy for the situation: “Realizing the extent of your grief and anxiety, it is not easy to express condolence to you who gave your loved one under circumstances so difficult that there is no grave at which to pay homage.”

After the war ended, the military tried to identify as many remains as they could. The success rate was low, given technology at the time. Sergeant Charles Langord was the only one identified from the five crewmembers aboard John’s B-25. A letter to Violet in 1950 expressed sympathy for the situation: “Realizing the extent of your grief and anxiety, it is not easy to express condolence to you who gave your loved one under circumstances so difficult that there is no grave at which to pay homage.”

John’s older sister Patricia, Carol’s mother, treated wounded Army soldiers as a flight nurse; Patricia and her mother were prolific letter writers, and her mother’s greatest sorrow was that she could no longer write to John. Despite her own grief, John’s mother put her arms around the family and led them in moving on. The family continued to work, attend Sunday Mass, and do the things that families do: dinners, birthdays, Christmas celebrations, going to the movies. The Holy Cross fathers on the University campus regularly offered Masses for John. John Sr. passed away in 1948. Violet remarried.

Carol grew up hearing stories about her uncle and seeing pictures of him. Every year on Memorial Day, the family headed to a local cemetery with the graves of ancestors dating back to the 1800s. While the boys clipped the grass around the markers, other family members decorated graves with flowers plucked from their garden. There was no grave to decorate for John.

Nearly all cultures memorialize their war dead, but the United States stands apart in its determination to “leave no one behind,” even decades after a soldier dies or is captured in combat overseas. This ethos, while not codified in any official military doctrine, has resulted in our modern-day combat search and rescue capabilities, along with an endless quest to find and identify remains of the fallen.

Nearly all cultures memorialize their war dead, but the United States stands apart in its determination to “leave no one behind,” even decades after a soldier dies or is captured in combat overseas. This ethos, while not codified in any official military doctrine, has resulted in our modern-day combat search and rescue capabilities, along with an endless quest to find and identify remains of the fallen.

Although nearly all downed or trapped personnel since the end of the Vietnam War have been rescued or had their remains recovered, more than 82,000 Americans are still missing from World War II, Korea, Vietnam, and other conflicts. The Pentagon’s Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) coordinates with hundreds of locations around the world while searching for remains, with the goal to provide the fullest possible accounting to families of the missing. In 2018, DPAA identified the remains of nearly two hundred personnel.

Part of the US obsession with rescuing personnel and repatriating its war dead surely stems from our ability to afford the people and equipment needed to do so. But no other wealthy country expends equivalent resources on the recovery of soldiers’ remains. These efforts seem to line up with the parable of the lost sheep. We rejoice more over the one we have searched for and found than the ninety-nine who were never lost and whom we may have put at risk to search for the lost one.

Ensuring no one is forgotten has a long tradition at University of Portland. Every Veterans Day for more than sixty years, University ROTC students have held a 24-hour vigil at the Praying Hands Memorial to honor those who died or are still missing, along with all who have served during wartime. On Memorial Day, Carol Leitschuh now has a place to decorate with flowers for John. She would like to thank the students in the Class of 1948 who built the memorial.

In the summer of 2018, Carol received a letter from the Army asking for a DNA sample. After reviewing military documents from the 1950s in her grandmother’s papers, she learned that there were three unidentified soldiers from the island where John died. One was subsequently identified, and the other two are now interred at a cemetery in the Philippines. However, a follow-up letter acknowledging receipt of her DNA noted, “The request for DNA sample does not imply there are recovered remains associated with your loved one.”

In the summer of 2018, Carol received a letter from the Army asking for a DNA sample. After reviewing military documents from the 1950s in her grandmother’s papers, she learned that there were three unidentified soldiers from the island where John died. One was subsequently identified, and the other two are now interred at a cemetery in the Philippines. However, a follow-up letter acknowledging receipt of her DNA noted, “The request for DNA sample does not imply there are recovered remains associated with your loved one.”

Given that DPAA identifies only about two hundred sets of remains each year, the chances of recovering John Carroll are very low. Many of the missing will never be found and are remembered only in the memories of loved ones, scrapbooks, or an inscription on a memorial. Words that adorn the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington Cemetery also pay tribute to the unidentified fallen: “Here rests in honored glory an American soldier known but to God.” Also known to us—a young man named J.H. Carroll Jr., forever etched in brick on the memorial at home on The Bluff.

EILEEN BJORKMAN is a retired Air Force officer and freelance writer. Her first book is The Propeller under the Bed: A Personal History of Homebuilt Aircraft; she is now writing a book about combat search and rescue, Unforgotten in the Gulf of Tonkin.

PHOTOS courtesy of Carol Leitschuh.

University of Portland

5000 N. Willamette Blvd.,

Portland, Oregon 97203-5798

503.943.8000

This website uses cookies to track information for analytics purposes. You can view the full University of Portland privacy policy for more information.