Nursing

Portland Magazine

February 15, 2020

ERNESTO LOPEZ, 75 YEARS OLD, was admitted to the hospital two days ago, after his wife had difficulty waking him up from a nap. Two weeks prior, he’d fallen and bumped his head on the coffee table, which caused a subdural hematoma (bleeding in the brain area) near his right temple. Mr. Lopez reports that he is perfectly healthy—hasn’t been to see a primary care doctor in more than 10 years. He smokes two packs a day, and his spouse mentioned that he drinks socially. He has a grown daughter and some grandchildren who live nearby. He has been a great patient, and he can’t wait to get home.

These are the details University of Portland’s student nurses know before entering the hospital room themselves.

The hospital room, fully equipped with IV drip and heart rate, blood pressure, O2, and respiratory rate monitors, is actually on University of Portland’s campus—in the School of Nursing’s new Simulated Health Center, a key element of the school’s new curriculum. Ernesto Lopez is being played by a professional actor (or a standardized patient, an “SP” in medical-acronym speak).

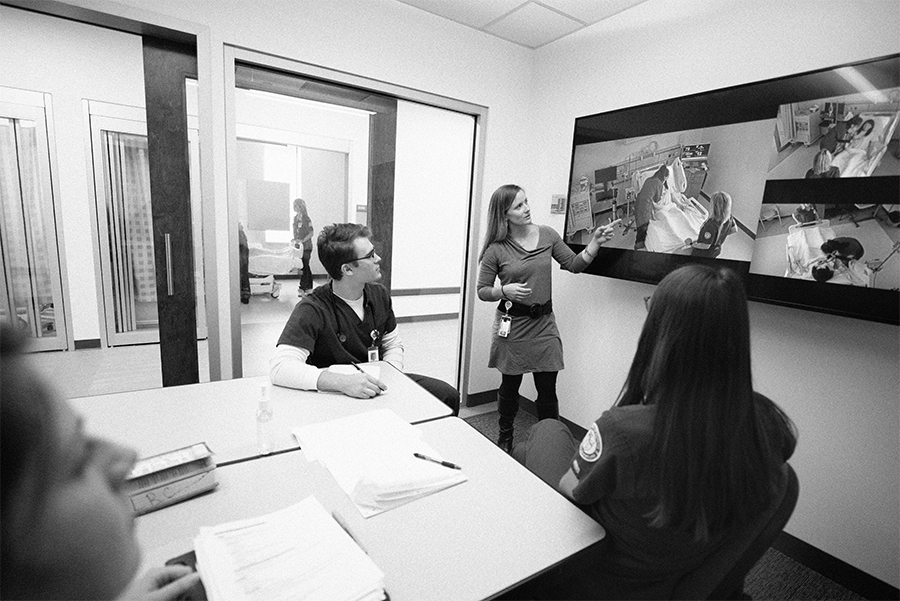

Two student nurses greet Mr. Lopez, while four others watch the scene from the debriefing room. Then the scene unfolds.

Humans being humans, Mr. Lopez throws them a few curveballs. He is a little disoriented. He keeps coughing and asking for a cigarette, and the nurse reminds him they’ve given him a nicotine patch to help him, but there’s no smoking in the hospital. His right arm isn’t exactly shaking, but he’s holding it close to his heart and moving it around.

“Who are you?” he asks.

“I’m your nurse,” one of the student nurses responds.

He tells the nurses that the previous nurses were rude.

“I’ll try not to be rude,” the nurse says. “Do you know where you are, Mr. Lopez?”

“I thought I was at home.”

They scan his wristband, and he says, “You’re trying to kill me.” Then he asks for another cigarette.

The nurses try to assure him that they are there to help him as they take his vital signs. His blood pressure is high, and he complains of a headache, so they administer some medication to alleviate that pain.

Then the nurses are called into the debriefing room to join an instructor and the other student nurses who have been observing and taking notes.

In this scene, the student nurses are the nurses; their observational skills are paramount, and they are making all the judgment calls.

“We’ve flipped the classroom,” Chris Blackhurst ’11, ’14, director of the Simulated Health Center, says of the new experiential and concept-based curriculum that invites students to do more hands-on learning from the start.

“They can practice their clinical judgment,” says Simulation Operations Manager Stephanie Meyer ’08. She compares the simulation setting with the in-hospital clinical setting, where student nurses’ responsibilities are more limited while they are still in training. In the simulation setting, “they can practice being a nurse versus practice being a student nurse where the preceptor is making all the calls.”

Through simulation, these student nurses also get the opportunity to experience patients with a wide scope of symptoms, depending on the scenes created by Michelle Collazo ’17, and the students can also revisit patients later in the semester, so they can see the progression of a patient with a particular condition. When a student nurse is in a hospital on a clinical rotation, they don’t get to control the patients or the symptoms that they see. If they have a whole day of patients with flu symptoms, those are just the cards they are dealt.

Another advantage of the simulation is that student nurses can make mistakes in a safe space. Should they have prioritized Mr. Lopez’s blood pressure over the headache? Did they miss an arrhythmia? Should they have prioritized tasks over trying to soothe the patient’s nerves? They get to practice all those moment-by-moment judgment calls that nurses make all day every day. And they also sometimes bump up against some unconscious biases they might have about, say, the elderly, or about those suffering from addiction. The debriefing instructors are trained to pull at the thread of these questions and guide the students to new understanding.

To observe the simulation, I sit in the tech room with Stephanie Meyer. After the debrief, the next two nurses get ready to enter the scene. Before they arrive, Meyer turns to me and says, “Are you OK with vomiting noises?”

I shrug. I have kids. I should be fine.

“It’s pretty loud.” She gestures toward the actor on the screen. “He’s good at it.”

The nurses walk in to Mr. Lopez leaning over his bedside, vomiting into a bag. They’d known about the blood pressure and the headache, but the nausea is new information. They arrange for the nausea medication. They take his temperature. They try to make sure he doesn’t get out of bed.

Mr. Lopez stops vomiting, but he is moving around on his bed, clearly uncomfortable.

One of the nurses notices something off about his heart rate and calls the cardiac telemonitor technician to verify that what she is seeing is indeed an arrhythmia. Good catch. They take next steps to address it.

Meanwhile, Mr. Lopez’s anxiety escalates. He scratches at his skin and complains about spiders crawling on the walls.

“Are you trying to poison me?” he asks, as the nurses hand him his anti-nausea medication.

At this point, the nurses know that Mr. Lopez is experiencing withdrawal symptoms, and they try to ask a couple more pointed questions about his drinking frequency, though they don’t really get a straight answer.

One of the nurses calls the attending physician to determine whether Tylenol or a different medicine would be better for a patient if they have concerns about kidney functions. They also discuss the dosage of anti-anxiety medicine.

Meyer, watching from the tech room and answering the calls as the telemonitor and the attending physician, and later as Mr. Lopez’s daughter, spent nine years working on the medical surgical unit at PeaceHealth Southwest Medical Center before coming back to UP as an instructor. She points at the actor playing the symptoms of withdrawal, and she says, from experience, “That’s very realistic.”

And so here is another benefit of the simulation. These scenarios don’t include code blue situations—the ones that might make for good TV. “These are regular challenges in an acute care setting,” says Meyer. Someone who gets a job on a medical surgical unit at a hospital will more than likely encounter a patient experiencing withdrawal symptoms. Now these students know how to look for it.

Blackhurst notes that a lot of what the student nurses might do—involving dietary needs, bathroom assistance— is important but might not always involve the critical thinking part of the job. Plus, Blackhurst says, many cities don’t have enough clinical placements. Simulations mean student nurses can gain a wider range of experience before they graduate.

This doesn’t mean University of Portland is moving away from onsite clinicals. Quite the opposite. The opportunities with clinicals are expanding too. The Dedicated Educational Clinical Model, started by former associate dean Susan Moscato ’68, has expanded, and University of Portland now works with 14 sites in the Portland area under the direction of Larizza Limjuco Woodruff ’08, Center for Clinical Excellence Director, who finds and develops new partnerships and opportunities for clinical education— some in hospitals and some out in the community.

The truth is there is such a wide range of career paths for nurses, and the opportunities are growing and diversifying. Their careers may never be in a traditional hospital setting. The new simulation lab and new curriculum are University of Portland’s way of responding to rapid changes in the health care field. UP wants to prepare nurses who are ready to work to minimize health care disparities and who will be leaders through today’s primary care shortage and the shift in care from hospitals to other outpatient and community settings. UP nurses will be on the front lines of all these changes.

Technology is also a big part of the changing landscape of health care. Not only do nursing students practice with telemonitoring and electronic records (and you notice that the student nurse scanned Mr. Lopez’s wristband and called the cardiac telemonitor tech), but there are new careers for triage nurses and telehealth nurses that will use screens and mobile technology to bring health care directly to people who need it. But these new technologies require different skills. How, for instance, do you assess a patient remotely or on a screen?

Telehealth might be particularly beneficial to patients in rural regions who don’t have access to a nearby hospital, enabling a patient and provider to have a timely screen visit with a specialist. “If a baby is born with complications in a rural area, requiring specialty care,” says assistant professor Kelly Fox ’90, who has been charged with creating the new telehealth curriculum, “we can use telehealth technology and potentially keep the baby at home versus transporting the baby to Portland.”

The telehealth classes will use University of Portland’s new telehealth suite for their own simulations, along with the new home health settings.

Time to check back in on Mr. Lopez. The third shift of student nurses enters the room.

With a little time, his anti-nausea and anti-anxiety meds start to work. He is a bit calmer, but he does start trying to get out of bed, which could mean a risk of falling. As they assess him, Mr. Lopez’s daughter calls, and one of the nurses picks up.

“I’m thinking about bringing my kids in to see their grandfather. Would now be a good time?” the daughter asks.

The nurse needs to update the daughter on the new information they have learned. Does the daughter know about the father’s drinking? How do you offer a status update with sensitivity? Would bringing the grandchildren in right now be upsetting to them? The nurse makes these snap judgments and responds.

JESSICA MURPHY MOO is the editor of Portland magazine.

University of Portland

5000 N. Willamette Blvd.,

Portland, Oregon 97203-5798

503.943.8000

This website uses cookies to track information for analytics purposes. You can view the full University of Portland privacy policy for more information.