Portland Magazine

April 15, 2020

For Grandpa Gabe

by Stephanie Anne Salomone

MY KIDS LIKE TO TELL ME that I’m a doctor, but not a useful doctor, and that’s true. When the flight attendant asks, “Is there a doctor on the plane?” they don’t mean a Ph.D., and they certainly don’t mean someone who is especially helpful only in a mathematical emergency. The COVID-19 crisis, though, could be the time that we P(hD)arents shine in the eyes of our children. We know things about things, we teach, and we have skills that, while not sexy enough to make exciting career day talks (research, reading graphs in scientific journal articles, data analysis), might come in handy when it comes to Common Core.

Except…not. Because unless I can make every math example into a fart joke, my boys aren’t interested in being taught by me.

Milo is working on proportional reasoning. Ratios. He’s getting more and more wound up because I’m asking him to reread the word problem. He is bright and just needs to slow down. “JUST BECAUSE YOUR DIPLOMA WAS SIGNED BY THE TERMINATOR DOESN’T MEAN YOU KNOW ANYTHING ABOUT TEACHING MATH!” my sixth grader bellows, and he’s right, in part. The then-gubernator of California did sign my doctoral mathematics diploma. Milo is also right that my mastery of a subject does not guarantee that I would be a strong teacher of that subject. But I have 23 years of student perception data on my side. I am a mentor to other faculty members. I may not have Mr. Universe-level awards, but I’m no slouch, either. Milo flounces. I stare back and raise one eyebrow, and he makes a grunting noise that all parents of preteens recognize as, “Fine. I’ll do what you say but I still think you are totally unreasonable.” His angst and insult is not worth it, but I’d like to take the moment to teach him about proportional response. I don’t. He solves the problem on his own. It turns out the denominator was 15, not 8.

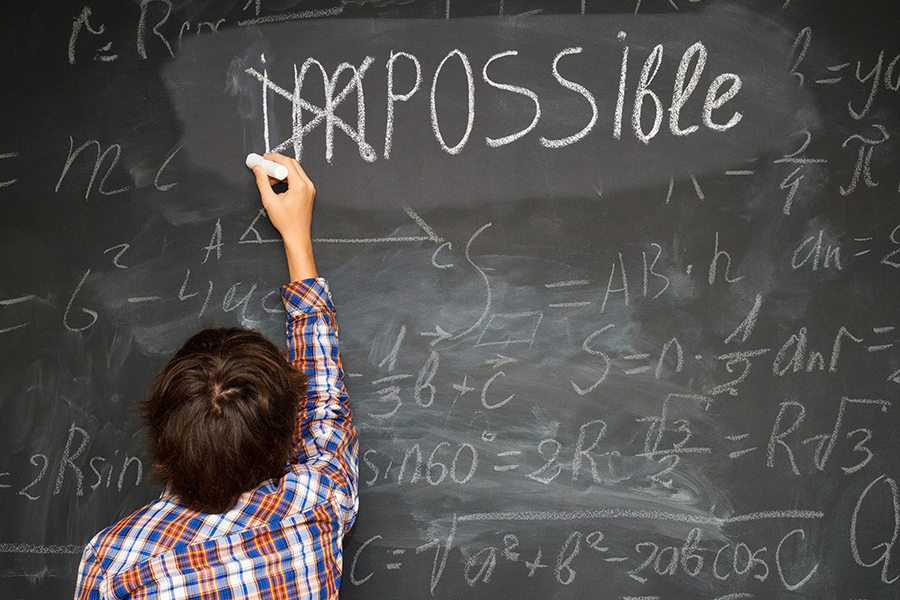

Jude, who is nine and has, for nine years, alternated unpredictably between who we call “Agreeable Jude” and “Contrary Jude,” has taken to writing IMPOSSIBLE next to the math problems he can’t solve immediately. “You know, some problems just take more steps,” I tell him, and he rolls his eyes and emphatically pushes his breath out his nose. Apparently he’s Contrary Jude right now. I try again, “If you ask me what mathematics is, I would say mathematics is breaking up a big problem into small problems, and then solving those. Maybe we can do that?”

“Fine, Mama, but could you at least make it interesting this time?”

Jude loves baseball so much that before the season starts he can name every Pilot player by number, position, and walk-on music, so I say, “One inning is one-ninth of a baseball game so what fraction is three innings?”

“It depends. This is a nonsense question. What if the game has extra innings like that time the Pilots played Gonzaga for seventeen innings and you made us go home?”

I’m at the kitchen table, because we don’t have a home office, grading proofs while my first grader, Theo, is melting down next to me because he thinks having to explain his answer to an addition problem is stupid because he knows his answer is right so why does he have to explain it. He is speaking at TOP VOLUME because we’ve been in the house together for going on four weeks, and my kids seem to think that the lack of being around others has rendered every member of our family temporarily hard of hearing.

“Well, actually,” I say, and then I laugh because when I get “well, actuallied,” I immediately tune out. So I start again, with a little enthusiasm, “Communication about why in mathematics is the best part! You get to be creative, and maybe draw a picture, or write a story, or connect it to something in the real world.” He looks at me blankly so I keep going because I’m sure I’m getting through to him. “It’s great to know math facts, but being able to explain why your conjectures are correct is really important. Why should someone just believe you? Why should someone believe me?” He blinked.

“You don’t understand, MAMA. And you DON’T KNOW WHAT YOU ARE TALKING ABOUT.”

Normally I would be able to brush off that slight, and let my inside voice handle it, because Theodore is six and I am…rational, but not today. Not in what is supposed to be my moment to shine.

“Pal,” I say in a way that makes me seem calm even though I’m really about to lose it, “I don’t want to toot my own horn, but I’ve won teaching awards at every institution I’ve taught at. And from the Oregon Academy of Science. And, you know, my students like me, and I really do know a lot of math, and if you’d just stop yelling at me, I’m pretty sure I can help you with this.”

He put down the pencil. He looked over at me. He smiled. I smiled. He was listening to me. I was getting through. I was teaching him. He looked me right in the eye. He took a breath.

“You said, ‘toot.’”

Stephanie Anne Salomone is chair of the University of Portland mathematics department and winner of the 2019 Outstanding Educator/Higher Education Award from the Oregon Academy of Science.

University of Portland

5000 N. Willamette Blvd.,

Portland, Oregon 97203-5798

503.943.8000

This website uses cookies to track information for analytics purposes. You can view the full University of Portland privacy policy for more information.