Portland Magazine

January 1, 2022

One UP professor’s observations of the art and resilience along the US–Mexico border, also known as La Línea.

Story and Photos by Blair Woodard

Borders between nations are human creations. They represent the limits of a national self, the line where the imagined division between “us” and “them” takes place. For so many reasons, borders are places of fascination for me. Liminal zones. Sites of change. Points of no return. Places of opportunity and hope as well as of pain and sorrow. I have been studying the human exchanges between border nations now for over twenty years, and I still am captivated by their stories. What side of the line you see as the “other” side, “el otro lado,” can determine so much.

The US–Mexico border is known as many things—gateway, frontier, escape, opportunity, separation, or simply as La Línea/The Line. One of the places along La Línea that I visit often is the Playas de Tijuana. These city beaches are in the farthest Northwest corner of Mexico. The district is made up of several neighborhoods and beaches that run south of the border for about a mile until colliding into the sheer cliffsides of the Baja Peninsula. The beaches are a destination for locals and tourists who come there to hang out, have dinner, swim, and celebrate quinceañeras. The beaches are a buzzing dynamic place where one’s senses come alive: the sounds of the surf crashing, norteño bands busking, kids laughing. You can smell the ocean, the fresh seafood, and tacos from the many restaurants that line the cliffside. The wooden planks of the boardwalk creak underfoot as people stroll along.

But Playas is not just a place to get away from the city; it is also heavily political and full of global and personal meaning. It exists along the portion of the US border wall that extends more than three hundred meters into the Pacific Ocean.

In the United States, on the other side of that wall, is Imperial Beach, which is deserted and under constant Border Patrol surveillance. The contrast between the vibrancy of the beaches in Tijuana and the vacant wetlands in the United States is telling.

As part of the contrast, the citizens of Tijuana have turned the border wall and the boardwalk into a living art exhibit. The art only exists on the Mexican side of the line, with murals expressing joy and hope as well as pain and sorrow. The wall is more than just a symbol of the relationship that the United States has with Mexico and the global south in general. It is more than just a barrier.

It is a sacred site. A place where crosses are erected and blessings are made. Where tears are shed and memories kept. Where hope for justice, empathy, and a better future is expressed.

I have been photographing these murals now for almost a decade, and I’ve observed that the wall itself is in many ways a living structure; as the ocean rusts it and wears it down, the United States keeps adding and rebuilding it. Because of these same forces, the artwork on the Mexican side is also con-stantly changing. The art fades with the salt air, and in some places, messages have eroded or been torn down. In other places, the messages have been painted again and again, layer upon layer. These constant changes turn an inanimate object into something that seems to have a life of its own through rebirth, decay, and eventual regeneration.

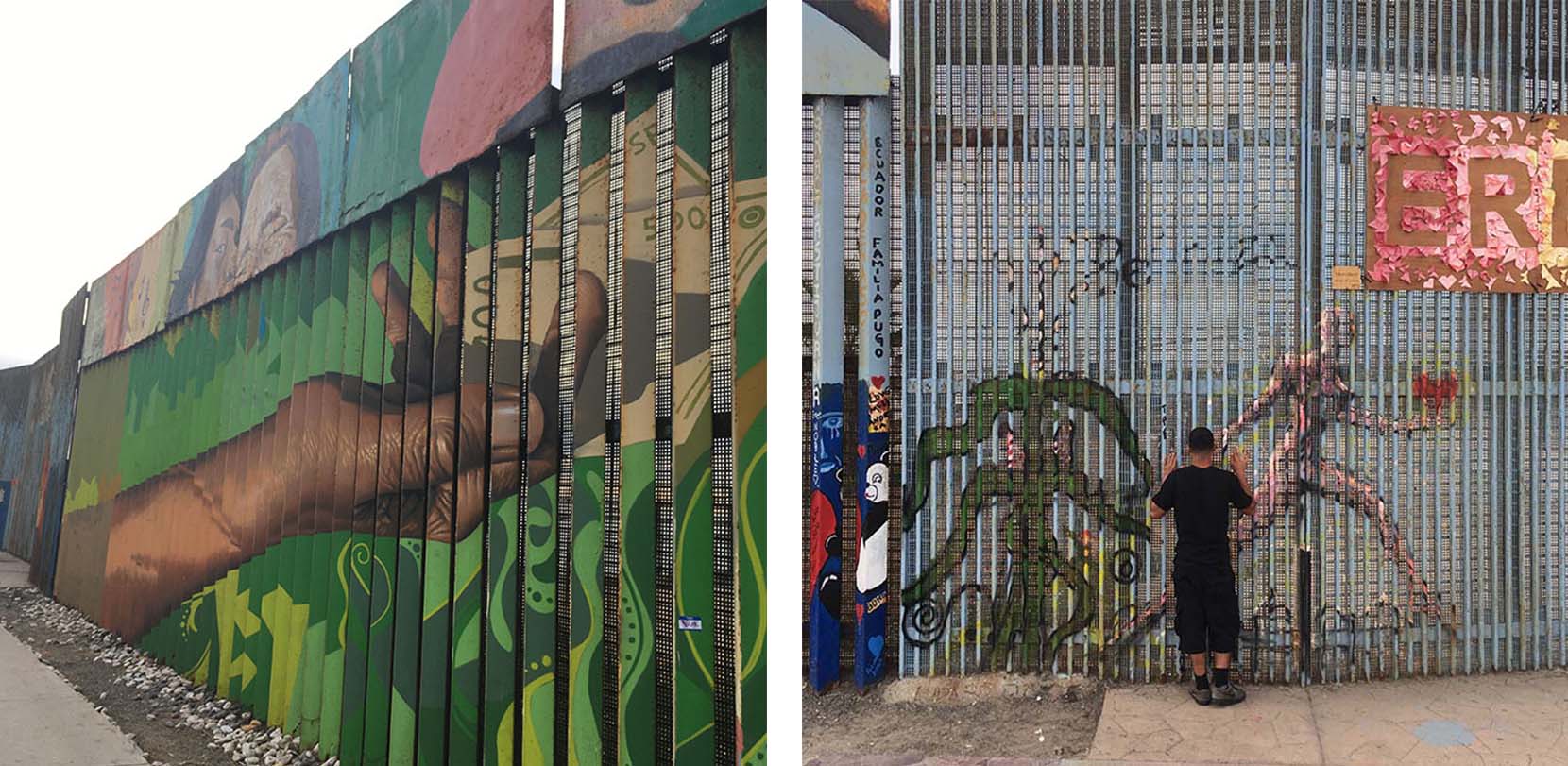

The murals vary. Some are overtly political. Others are more personal and reflect on a specific event or family member. Some are intricate and professional, formal art projects that have been funded either in the United States or in Mexico and created by teams that sign their work. Others appear to be more spontaneous and makeshift. All are impactful.

Starting at the ocean and moving inland, there are currently two large mural projects. The first is of several faces—portraits of 15 people who have been deported, individuals from all walks of life. This project, known as the Playas de Tijuana Mural Project, is under the direction of Lizbeth De La Cruz Santana, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of California, Davis. Some of those depicted in the portraits are the artists themselves. QR codes accompany these faces and tell their stories and many others in digital form.

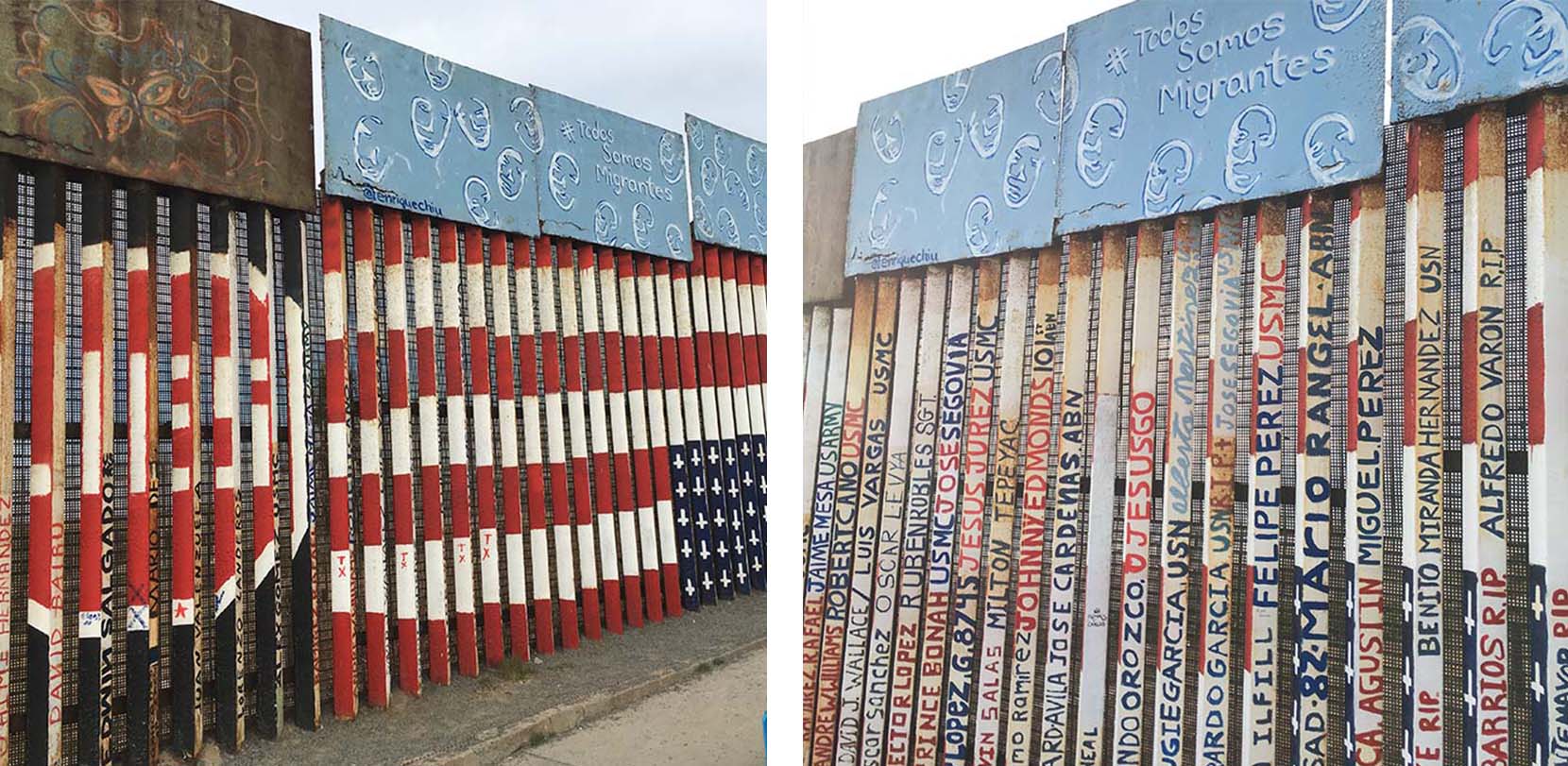

Another mural portrays an upside-down US flag with crosses instead of stars and a stop sign with the word “Lies.” The upside-down flag is an international sign of distress and is dedicated to the US military veterans who have been deported to Mexico. Their names are written on the slats of the wall in the opposite direction as the flag. On a recent visit I witnessed a deported US veteran painting more names and the word “Repatriate.” He expressed hope that this will be the last time he needs to paint on the wall. Recently the Biden Administration has pledged to bring these veterans back to the United States.

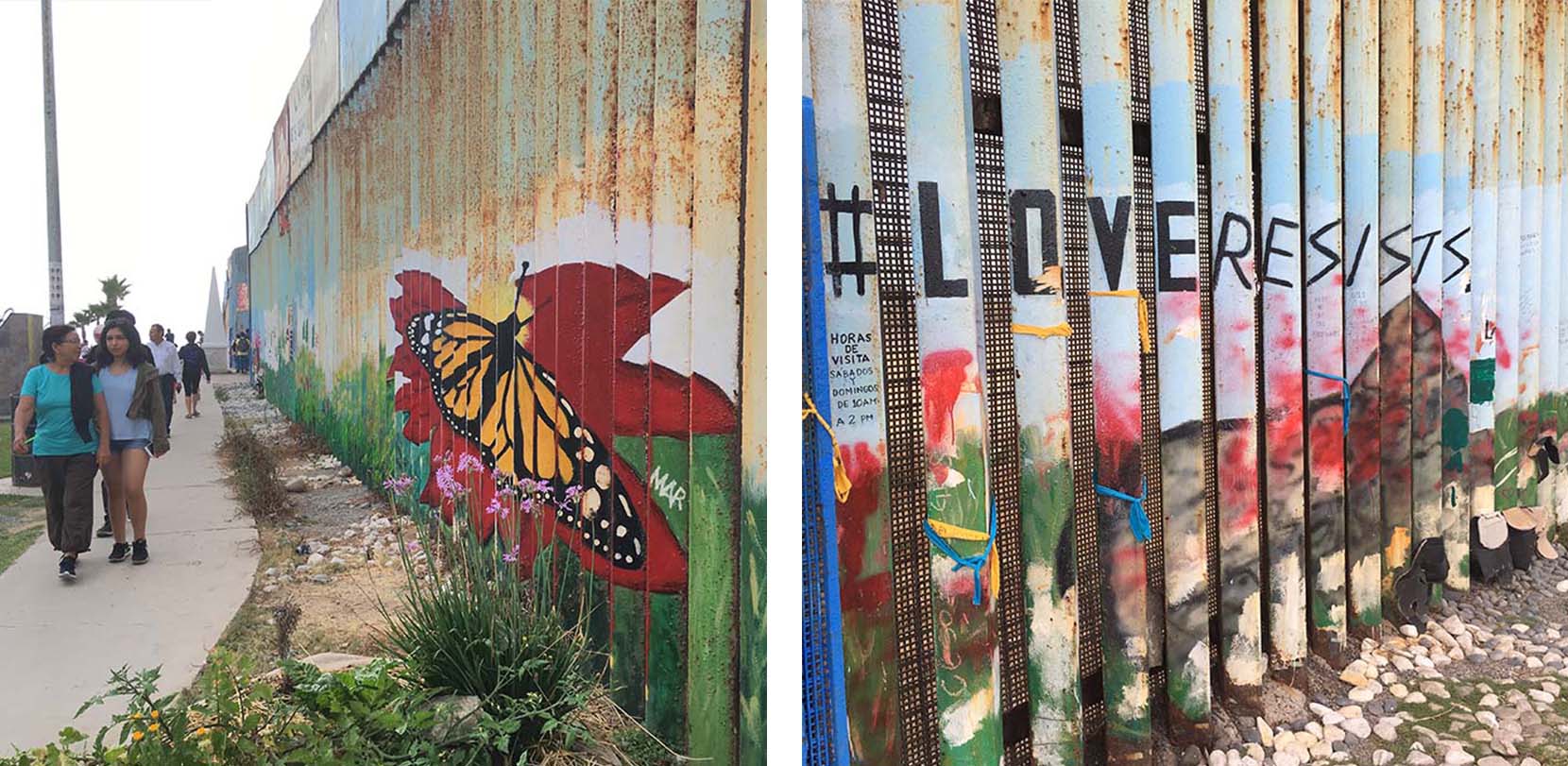

As you walk along the wall there are crosses and handprints. The names of loved ones. Posters and flyers with the photos of people who are “desaparecidos,” disappeared. You come to a doorway that seemingly no longer opens. On the door are a large heart and a single word: Love. Other words blanket the wall: Empathy, Justice, Peace. Paintings of animals, both life-like and cartoon, adorn the barrier throughout: birds, whales, and pandas. Next, a Bansky-esque figure with a rope and grappling hook. Then, flowers and human figures.

One of the murals that I’m particularly fond of—a monarch butterfly—has been preserved and repainted. The monarchs are renowned for their annual migrations both north and south. Some of the butter-flies fly over three thousand miles from the United States to Mexico. They are the only butterflies known to make a two-way migration like many birds do. The beauty of the butterfly stands in stark contrast to the wall and makes the obvious point that no wall can stop a butterfly—or the will of people to overcome obstacles to obtain justice and a better life.

All the murals along the wall form a type of collage. A mosaic of different statements and emotions, which all come together to form a singular picture of resistance. Because the slats of the wall are triangular, you may see something in one direction that you have not seen in the other. It’s also telling that you can’t see the murals if you’re looking at the wall straight on. One has to look at the barrier from an angle for the images to appear. This is very emblematic of the relationship between the United States and Mexico on many issues. In some ways things that appear to be straightforward really can’t be seen unless you take into account different angles, different perspectives.

Ultimately, the border challenges us. The Line, La Línea, confronts us about how we view ourselves, other nations, other peoples, and what it means to be on one side of the line or the other. Part of what I believe we need to do as human beings is try to see people’s stories from the other side. Part of why I continue to go to the border is to look at the United States from the other side. What I’ve found is that in many ways “the other” side has a better view and a deeper understanding of “us” than we can possibly imagine. The opportunity to cross the border and to look back, to try to see oneself from another’s view, is a privilege that I do not take for granted. It informs so many parts of who I am—my teaching, writing, politics, and personal relations. Attempting to see ourselves and others from el otro lado is, in my opinion, a key to understanding. Seeing the line from the other side serves as a reminder that walls don’t work, that fear will not win over love, and that no wall will dampen the human spirit, or keep butterflies from flying home.

BLAIR WOODARD is an associate professor of history and environmental studies at the University of Portland. His research and teaching interests focus on US–Latin American relations and popular culture.

University of Portland

5000 N. Willamette Blvd.,

Portland, Oregon 97203-5798

503.943.8000

This website uses cookies to track information for analytics purposes. You can view the full University of Portland privacy policy for more information.