Portland Magazine

March 28, 2024

Mike Burton ’71, ’74 wants the US to clear the bombs it left behind in Laos 50 years ago.

Story by Jessica Murphy Moo

Photo credit: Adam Guggenheim

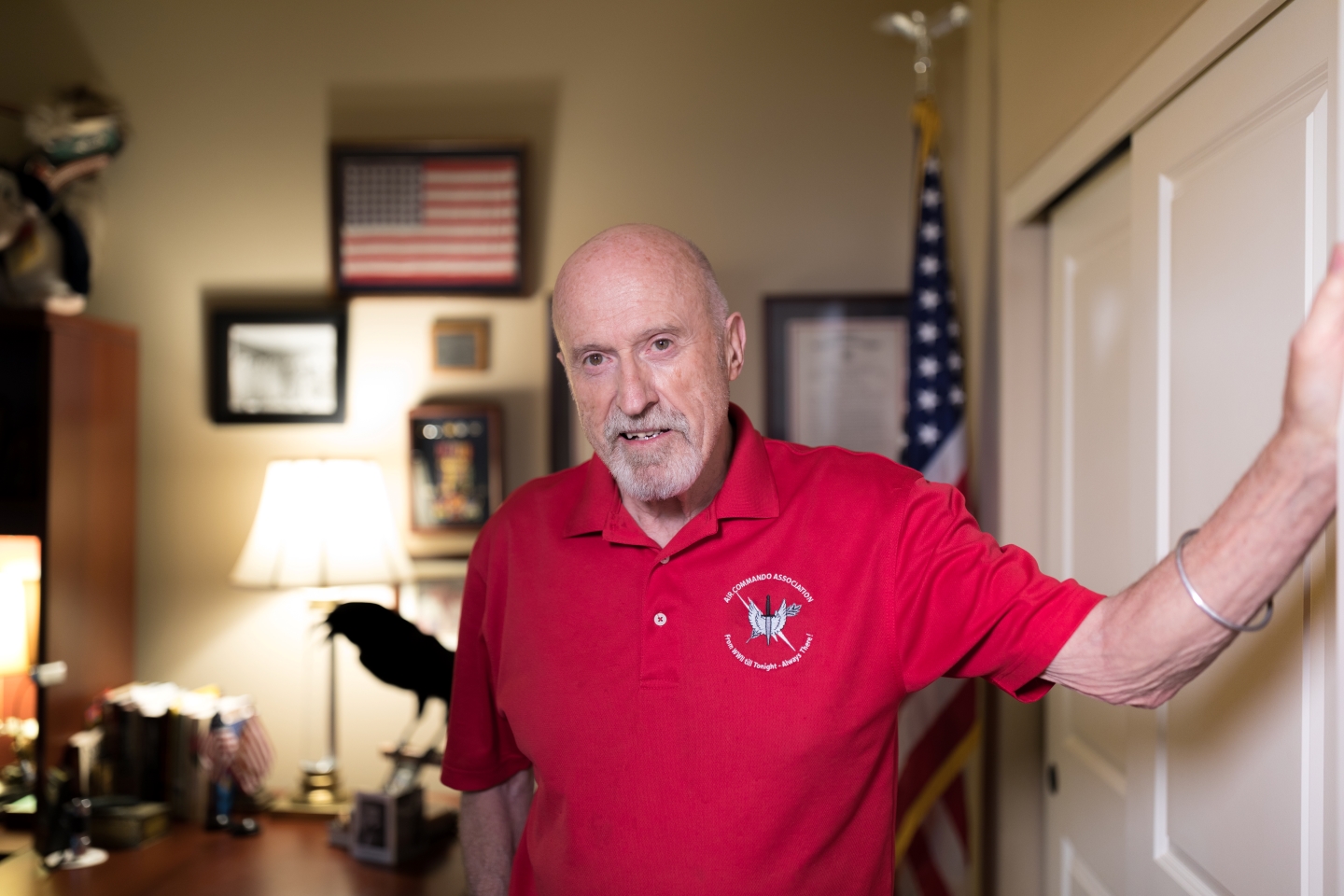

ETCHED ON THE bracelet Mike Burton wears on his left wrist are the words “made from bomb parts.” He bought the bracelet on his last trip to Laos, the Southeast Asian country that shares its eastern border with Vietnam. A US Air Force veteran, Mike is among those who dropped bombs in Laos, during what became known as the CIA-run “secret war,” which lasted from 1964 to 1973.

Mike doesn’t need the words on that bracelet to remind him of the war or the remnants that have lasted more than 50 years—his memories and PTSD and physical ailments have been reminders enough. But the bracelet does symbolize his commitment to advocacy work. He spends a lot of time informing elected officials in Washington, DC, about the issue of unexploded ordnance (UXO) that the US left in Laos. The type of ordnance used most frequently in Laos are known as cluster munitions. Of the 270 million cluster bombs dropped on the country, about 80 million didn’t detonate, and they continue to harm and kill innocent people today. Mike believes the United States is responsible for funding the removal of the UXO. And he also believes that cluster munitions should no longer be used in war.

As chairman of the board of Legacies of War—an advocacy and educational organization led by a fiercely committed team of Lao-Americans—Mike uses his experience in both war and government to bring attention to the UXO issue, so that the people of Laos might move on from the war that ended half a century ago.

Mike has now been to Laos three times—during three periods of his life— though in some ways he has never left. “I couldn’t shake the place,” he says.

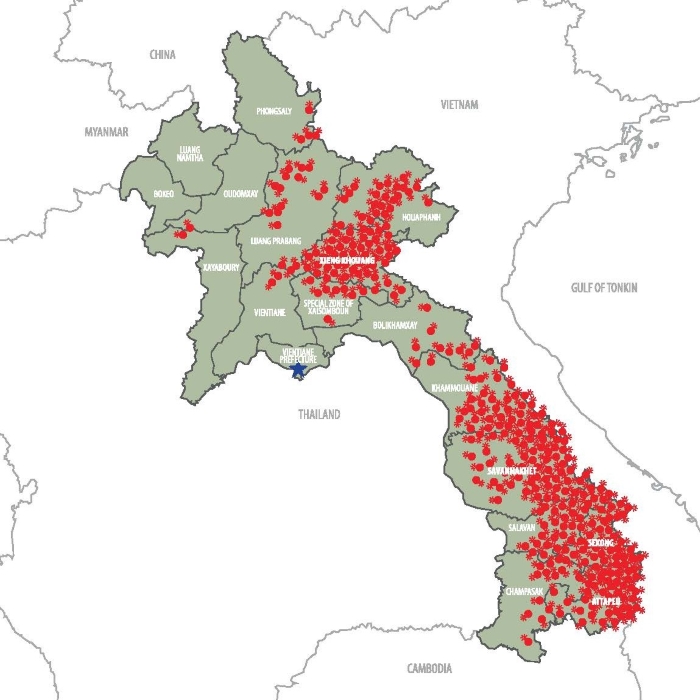

(Left) From 1964 to 1973, the US dropped more than 2.5 million tons of ordnance on Laos. Bombing occurred in every province, but was heaviest in the north and east. (Right) A half-buried cluster munition.

THE SCALE OF THE PROBLEM

Laos has the unfortunate distinction of being the most bombed country per capita in the world. Since Legacies of War was founded in 2004, the team has built awareness of the UXO issue and continues to find ways to make the massive scale of the problem comprehensible to the American citizen, who may not know about the “secret war” in Laos. Americans also don’t risk their lives when they plant a garden, don’t stumble across bomb craters in their neighborhoods. They’re not accustomed to seeing children missing limbs from bombs.

The US dropped more bombs on Laos than on Japan and Germany in all of World War Two. Over nine years, at least 2.5 million tons of ordnance were dropped on a population that was at the time just more than two million. That’s two thousand pounds per person in a country roughly the size of Oregon state.

Those that didn’t detonate on impact, more than thirty percent, remained in the ground. Some of those bombs now live under 50 to 60 years of growth and are sometimes disinterred when farmers clear land for crops. When an area floods, bombs show up downstream. About the size of a tennis or bocce ball, they are often called “bomblets” or “bombies.” They’re small enough for a curious child to pick up and hold in one hand. Kids learn songs in school that warn them about the dangers of the bombs.

And still, at least 25,000 civilians have been killed or injured from the bombs since the end of the war. Some 40 percent of the injuries have been children.

Sera Koulabdara, CEO of Legacies of War, remembers the bomb that changed the trajectory of her life. She was about six years old when a family came to her home outside Vientiane, frantically knocking on the door, holding their daughter. A bomb had exploded near her while she was walking home from school. To save the girl’s life, Sera’s father, a surgeon, had to amputate her leg. The incident made Sera’s family realize that they needed to leave. No place seemed safe. They moved to the US in 1990, settling near Washington, DC, where they had family who’d fled Laos after the war, in the ’70s.

“It’s a crisis,” she says, of the unexploded ordnance. A present-tense crisis.

Danae Hendrickson, Lao-American chief of mission advancement and communications for Legacies of War, describes the impact of demining work in a very simple, concrete way: “Every piece of ordnance that is removed is a life saved.” At least one life.

On August 4, 2023, The Laotian Times reported that two children—one a 10-year-old boy, the other a 5-year-old girl—died from an explosion. According to the report, a family member had believed it was scrap metal that could be sold. Two other children were injured in the blast.

Mike Burton (second from left) in a Laotian village, accompanied by a member of the US embassy and translators. He was ordered to wear plainclothes. “We weren’t supposed to be there.”

THE ASSIGNMENT IN LAOS

Mike was 26 years old in 1966, when he received his assignment to Southeast Asia. An Air Force captain, he’d already served in the Congo. On his initial intake form, someone mistakenly checked the box that said he spoke French, and Mike believes this was why he was sent to two former French colonies. Mike doesn’t speak French and he never met anyone in Laos who did.

When he received the paperwork that he was being called up, he looked for the APO (air postal code) to see where his assignment might be. His was stamped “confidential.” He assumed he was being sent to Vietnam. He bought into the Domino Theory and that the US was obligated to fight to stop the spread of communism, that stability for democracy in the region would lead to greater national security.

“I was a believer,” he says. So he followed orders and got on the plane, but when he got to Saigon, he was directed to get on another plane continuing west.

Officially, the US had agreed not to interfere in Laos. In 1962, in Geneva, along with 13 other countries, the US had signed the International Agreement on the Neutrality of Laos. Starting under President Kennedy, the US and several other countries violated this pact. The US trained and armed anti-communist guerilla forces in Northern Laos and began their bombing campaign. The goal was to stop the expansion of communist forces from the north (both the Pathet Lao and the North Vietnamese) and to stop the flow of goods, personnel, and munitions from Hanoi to Saigon along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which was almost entirely in Laos.

After stopping at several other bases in Thailand, Mike learned he was stationed in Nakhon Phanom, Thailand, on Laos’s border, west of the Mekong River. “I did not know where in the hell I was,” he says. He was surrounded by old planes, T-28s and A-26s. “I thought I’d gone back in time to World War Two.”

He soon learned that he was part of the 56th Air Commando Wing, and part of the special operations to train Lao, Hmong, and Thai pilots. He would join them on information gathering missions and help direct them to the landing sites in the region and on bombing sorties. On his second day on the job, he was given a 25-year nondisclosure agreement. He signed it. Soon after that he learned that the CIA was calling the shots for a war in Laos that the American people knew nothing about.

Everything about his assignment was confidential. Congress had not signed off on this war. Among his responsibilities was acting as a director of information on the base, a job that became an exercise in creative euphemisms. He filed a number of reports about bombing sorties “over Southeast Asia.” It was also a textbook example of irony. He was an information officer who was not permitted to allow information to get out. He was ordered to make a brochure about the base in Thailand, but forbidden to mention what they were doing there. When a higher-up learned that US planes were featured on the cover, he was ordered to destroy the brochures altogether.

Before Christmas one year, Bob Hope came to visit the troops. He asked Mike for potential material. Mike told him everything was classified, so he’d have to use that. Hope ran with it. He opened the show saying, “Well, I guess I’m not really here. And neither are you.”

Mike couldn’t see the big picture of what the US was doing there. He was in the eye of the storm. “I started to ask, ‘What am I doing here?’ ” he says.

Conflict in Laos between the Royal Laotian Government and the communist Pathet Lao was not new. Ever since France had left the region in 1954, there had been a power struggle, attempts at appeasement and coexistence, and periods of civil war. By allying with a group that had already been fighting against the Pathet Lao, the US was using the divisions that were already there to advance its own goals.

Before the 1962 Geneva agreement, the CIA was already talking to General Vang Pao, of the Royal Lao Army. General Vang Pao had fought against the Pathet Lao and, before that, had fought alongside the French against Japan’s advances into Laos during WWII. He was Hmong, an ethnic group in Laos that mostly lived in the country’s mountainous region to the north. With financial backing from the US, Vang Pao was able to recruit Hmong soldiers to fight the war the US wanted him to fight. For the most part, the US stayed in the air.

Mike was responsible for maintaining relations with the Thai government and to act as a liaison with the local people at the landing sites in Northern Laos. In plainclothes, Mike would visit Hmong villages and, with the help of translators, ask people what they needed. If they needed rice, they’d arrange for a rice drop. If they learned there was an outbreak of dysentery, he’d arrange to set up a privy system for waste disposal. It was during these many conversations that he learned that not all Hmong wanted to fight the communists. Many civilians wanted to be left alone.

He once met with an influential teacher, a kind of elder in the community. When Mike asked him what he needed, the man said, “I want you to leave. This isn’t our war. And you’re going to get us killed.”

The man was right.

Weeks later, Mike was flying over an area nearby and learned that this particular village was under attack. They flew over to see what they could see and get help. They landed. The mortar fires stopped. Mike saw that the teacher had been killed in the public square.

It is a painful and grisly memory—one he tells now, though he kept it buried for many years.

DEPARTURE AND RETURN

Mike’s first mission in Laos ended in 1968, when he was injured during a surveillance flight near the Ho Chi Minh Trail. He was in the backseat of a T-28; the pilot was from Thailand. They were fired upon by 37 mm anti-aircraft guns, so the pilot took altitude—“this was the right thing to do,” Mike says— but they flew into a sheet of flack. The aircraft was hit. Mike was hit twice, once in the abdomen. There were no ejector seats in these planes. They broke open the canopy, and Mike managed to jump and deploy his parachute. He landed in a tree, and injured his head in the fall. Local Hmong scouts found him and cut him down. For sterilization, his abdominal wound was packed with sulfur, and Mike was airlifted to Hawaii for surgery. The pilot and the plane were never recovered.

When he returned to the US, he says, “If I was still for five minutes I’d start thinking about the war.” The nightmares began. “And it didn’t have to be the night. I’d recall things.”

Mike can’t pinpoint when the PTSD started, though he describes the feeling this way: When you’re away, in the theater of war, “Everyone says, ‘I want to go home.’ But you don’t quite get there.”

It would be more than three decades before he sought help.

After physical rehab at the Wright- Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio, Mike moved to Oregon. He thought academia might be a career path, so he enrolled in a graduate program in history at University of Portland and earned an MA. In his time on The Bluff, he helped with the ROTC Airforce Detachment 695 program and even co-taught a Sherlock Holmes class with Professor Jim Covert. After also completing his Master’s in education, he was called back up to return to Laos. It was 1974.

“I thought the war was over,” he says. But he was asked to sign another 25-year NDA.

He was stationed in Bangkok this time, and was charged with evacuating people from Long Tieng, the main military base up north. They evacuated more than 2,500 soldiers and family members, including General Vang Pao, but more than 35,000 were left behind on the base. In a PBS documentary on the war, Hmong historian Mai Na Lee says that, for many Hmong civilians, the war really began after the US stopped fighting. They were left to fend for themselves as Pathet Lao advanced. Many Hmong refugees crossed the Mekong River into Thailand and waited to be sponsored to move to another country. A quarter of the entire population of Laos—approximately 750,000 people—became refugees.

Mike returned to Portland and has spent 35 years trying to come to terms with the role he played in the war.

He began working with Lao and Hmong refugees, helping them secure housing, education, and employment in the Portland area. With Hmong leadership, he took part in establishing IRCO, the Immigration and Refugee Community Organization, which serves refugees from all over the world.

One of the people Mike worked with was Lee Po Cha, now the executive director of the organization. His uncles and father were among those recruited by the CIA to fight in the special guerilla forces, gather intelligence, and rescue downed pilots—like Mike—for the American government. His uncles came to Oregon in 1976, and Lee and his family came in 1978. Lee was a teen at the time. He says he was one of about six people in the region who were able to translate for the Hmong community’s 6,000-plus refugees. His phone rang off the hook. Sometimes answering it was too much to bear—he learned that the 5 a.m. calls never came with good news—but he did his best to direct people to services.

As the years passed, Lee sometimes partnered with Mike, in Mike’s new role as a politician. Mike served in Oregon’s House of Representatives and later as executive officer for the Portland Metropolitan government. Lee says Mike sponsored the Refugee Child Welfare Act, which helped to guard resources and keep refugee children in family homes, rather than in the Oregon foster care system.

“Mike has had a relationship with refugees for a long time,” Lee says.

B-52 Bomber dropping ordnance

THE TRAUMA OF WAR

Mike may have retired from the Air Force as a colonel after 38 years of service, and he may have thrown himself into running for public office, but his war experiences never left him. There weren’t really any official supports at the time for dealing with war trauma, so he kept his experiences “stuffed in his boot.” This took a toll on him, physically and psychologically. Even in 1995, when the government declassified information about the war in Laos, he found he wasn’t comfortable talking about it. “I ended up drinking a lot,” he says. He also had excruciating back pain, walked with a cane, and couldn’t feel his feet (it was later determined that his exposure to Agent Orange is part of the reason), so he was taking opioids “by the handful.”

He finally called the veterans hotline in 2011, during a particularly tough period in his life. He’d resigned from his job, was followed by legal troubles, went through a second divorce, and was arrested for a DUI. During this tumultuous time, his war nightmares returned.

“I was depressed,” he says. “I called the hotline and said, ‘I need to see you.’ And I went in the next day.”

They worked on his physical pain first—he had his first of four back surgeries. And he was given supports for dealing with his opioid addiction and his drinking.

He was working with two therapists at the same time. One asked him to tell his story. He sat down and typed it all up for them, as best as he could remember. Then the therapist asked him to slow down, to write everything by hand. They went through it all, bit by bit, memory by harrowing memory. He dealt with his grief and guilt and his “woulda, shoulda, couldas,” as he calls them. He started to come out from under the things in his past that he couldn’t change.

He also started to be able to recognize the triggers. For a time he couldn’t handle the texture of rubber because it reminded him of body bags. The recent death of Kissinger also brought back a host of feelings and memories.

He sometimes meets with veterans in the Pacific Northwest to guide them toward benefits they and their families are due and toward the supports that have helped him. He wants veterans who are struggling with PTSD to know they are not alone.

Volunteering for Legacies of War—the purpose of the work—has been an important part of his path forward.

An example of bomb craters still present today. This aerial was taken in 2022, over the same province as the Plain of Jars, now a protected UNESCO Heritage site. Photo credit: Kaikeo Saiyasane/Xinhua via Getty Images.

UXO IN LAOS TODAY

In fall 2022, the Legacies of War staff returned to Laos. The organization feels it is important for staff and Congressional delegates to meet with government officials there and see the UXO issue firsthand. This was Mike’s first time back since 1975.

After meetings in Vientiane, the capital city, they flew over the Plain of Jars, an ancient burial site (500 BCE to 500 CE) in Northern Laos that’s now a UNESCO Heritage site. Mike says he saw bomb craters on the landscape and felt a deep sense of melancholy. “It came back to me,” he says. “I lost a couple buddies there.” And he also has regrets. “I didn’t have any understanding,” he says, of the site’s cultural and spiritual significance. The only thing they knew was that the site was close to a strategic area.

The Legacies of War staff later joined a team from the Mines Advisory Group (MAG) to clear some bombs.

On a Fall 2022 trip to Laos, Mike Burton accompanied a member of the Mines Advisory Group, as they cleared bombs in the region.

Demining is slow, laborious work. There is no technology that can do it on a large scale, so it is painstaking human labor, a person holding a bomb detector and scanning an area inch by inch. And the sites are often alarmingly close to villages and farms. The Legacies of War group watched the team locate a bomb, carefully dig around it—usually about four to six inches underground. On the day they visited, the deminers asked Mike to identify one of the bombs they found that day. He looked in the reference book he had with him. It was a cluster munition, a BLU-17.

Then, in preparation to detonate it (the only way for them to remove the active ones is to blow them up), they hooked a wire to the bomb and rolled the wire out a safe distance of 1,000 yards. They announced over loudspeakers to everyone in the region to clear the area. The farmers and villagers were warned to stop their work and get a safe distance away.

Mike saw that some of the farmers in the area didn’t stop working. It struck him how accustomed they were to this disruption—they still had work to do, even if they were at risk. He also saw a home whose construction had been stopped halfway because they’d found pieces of metal during the construction.

From the “ping” of the metal detector to the explosion was about an hour and 15 minutes. “It really became set in my mind how difficult all of this work is, how big a problem, and how we might not ever get all of the bombs out.”

During their visit that day, the MAG team found eight bombs.

While it can seem insurmountable, representatives from the HALO group doing the clearance work have stated that it is also a problem that can be solved.

“We remain hopeful,” Danae says. Danae was on this fall trip as well. She was struck by what it means for a US veteran and the people of Laos to do this work together. “It was momentous to see Mike walking with Hmong-Americans,” she says. “It was a picture of how far we’ve come to be reconciled, where we can walk alongside each other on this land and heal and advocate together.”

Left to right: Lee Po Cha, Mike Burton, and Sera Koulabdara, CEO of Legacies of War. Photo Courtesy of Legacies of War

THE WORK AHEAD

Mike doesn’t believe in redemption. But he does believe that there is work he can do. And these days there seems to be a lot of work for him to do. He’s busy.

Cluster munitions have been in the news more than usual recently. Both Russia and Ukraine are using them in their war. Legacies of War has urged the public and elected officials to learn from Laos and to step up pressure to stop these munitions from being used in war. One hundred sixty-four countries have signed the Mine Ban Treaty, and 123 are supporting the Convention on Cluster Munitions. The United States has not. The US recently sold the bombs to Ukraine. Mike wrote an op-ed in USA Today on the issue, urging the Biden administration to reconsider its policy.

He recently joined Danae—they both live in Washington State—to meet with Senator Patty Murray’s staff. In these spaces, it’s clear that Mike—as a former representative—is in something of a comfort zone, and it’s also clear to Danae that having constituents who are both part of the Southeast Asian diaspora and US veterans helps strengthen the message. Together, they updated Murray on the upcoming delegate trip to Laos and on a bipartisan bill (bipartisanship is still possible!) introduced in both the United States House and Senate last year.

The bill is called the “Legacies of War Recognition and Unexploded Ordnance Removal Act.” It proposes that the United States should recognize those from Vietnam and Laos—like Lee’s relatives—who worked for the US military during the war. It also proposes that the US should increase the financial commitment to the clearance of UXO in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos over the next five years. If passed, the funding would be $100 million annually for five years for the removal of unexploded ordnance in the region.

Photo credit: Chris Brecht

These days Mike wears another bracelet on his right wrist. It’s also from Laos. It’s a dragon made of interlocking metal pieces, not from harvested bombs.

There is a Laotian legend about the water dragons called “naks.” Sera grew up hearing about these naks from her grandmother, how they lived in the Mekong River and protected the people of Laos. “She told me,” Sera says, “how we had to be strong because we were descendants of the water dragon.”

It is safe to say the people of Laos would like to be known to the world for reasons other than the bombs dropped on them more than 50 years ago—for the roots of their ancient civilization; for the rich diversity of ethnicities and languages and cultures and religions; for their agriculture or their coffee; for their cuisine and the natural beauty of their land; for their kindness and resilience; and for the contributions they might be making more robustly if the country had not been hobbled by the contamination and dangers littering their ground. It has been a difficult country to invest in because the dangers persist.

Still, the Legacies of War team has made progress toward a safer Laos. When Sera was a child, there were no demining efforts happening at all, other than farmers doing it themselves, and there was no US funding toward UXO clearance. Now there is. There is movement. Later this year, Mike and Sera will head to Washington, DC, together to raise awareness among our elected officials on the issue of unexploded ordnance in Laos. They will be there to support the work of Legacies of War, and they will share their stories.

“He’s very brave to do it,” Sera says.

JESSICA MURPHY MOO is the editor of Portland magazine.

University of Portland

5000 N. Willamette Blvd.,

Portland, Oregon 97203-5798

503.943.8000

This website uses cookies to track information for analytics purposes. You can view the full University of Portland privacy policy for more information.