Portland Magazine

February 13, 2020

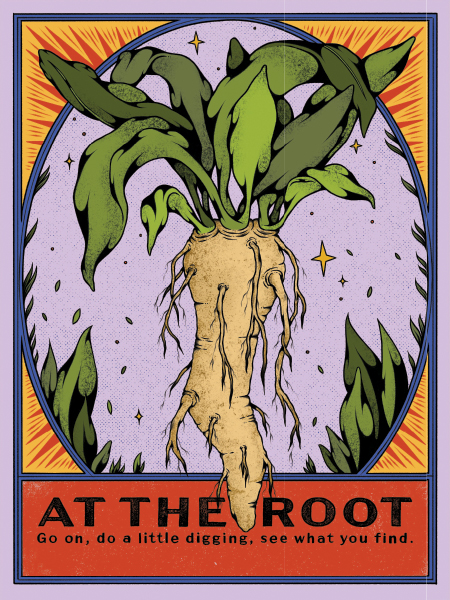

THE BOTANIST CARL LINNAEUS called it Amoracia rusticana, words whose Celtic roots mean “near the sea” and “of the country.” One strains to understand how any human could possibly have settled on such benign descriptions after having gazed upon the gangly protuberant taproot of a horseradish plant. Cut through its knotty skin—its color a blend of latte and hazelnut—and you expose hard white flesh. You release a pungent aroma that will open wide the most stubborn of sinuses or leave you gasping, as though your nasal cavity has experienced a surprise gas attack. Nothing of the horseradish suggests the salty ocean breeze of Normandy or the musty earthy loam of Iberia.

THE BOTANIST CARL LINNAEUS called it Amoracia rusticana, words whose Celtic roots mean “near the sea” and “of the country.” One strains to understand how any human could possibly have settled on such benign descriptions after having gazed upon the gangly protuberant taproot of a horseradish plant. Cut through its knotty skin—its color a blend of latte and hazelnut—and you expose hard white flesh. You release a pungent aroma that will open wide the most stubborn of sinuses or leave you gasping, as though your nasal cavity has experienced a surprise gas attack. Nothing of the horseradish suggests the salty ocean breeze of Normandy or the musty earthy loam of Iberia.

The Germans call it meerrettich, or “sea root.” Awhile back someone in England mispronounced it “mare radish” and then, given that language can sometimes be lazy and slipshod, someone decided to call it “horseradish.” (Who knows why that farmer or his neighbor might have thought—as they shaved the root into a wispy pile of scob to be ground with mortar and pestle and mixed with salt and vinegar—this root should be identified with a female equine? Nothing feminine about this stubby gibbosity.) Later, muuuuch later, horseradish would become slang for heroin, which makes sense. It can be deadly. Horses, ironically, will die if they eat the leaves of the horseradish plant. One of its active compounds, allyl isothiocyanate, is found in mustard gas. With horseradish, you’re playing with pungent, hot, peppery molecular fire.

At the Seder meal during Passover, Jewish families gather at tables at sundown, light a single candle, and begin their prayer with “Baruch Atah Adonai…” (“Blessed are you, Lord our God…”). And so they recall the night the Lord, with a mighty hand, liberated their ancestors from the yoke of slavery and how at dawn’s first light they began, triumphantly, their Exodus from Pharaoh’s Egypt. Part of the Seder ritual involves the eating of maror, that is, bitter herbs—horseradish—so they would always remember what oppression and humiliation and suffering tastes like on the tongue. My brother once gave my unsuspecting nephew—who was still in a high chair at the time—the tiniest sliver of an ounce of horseradish one day. Of course, the boy’s face turned an unnatural shade of reddish purple, and he screamed for a half hour. I was told later my brother’s cruelty so enraged his wife they almost separated. When I consider my nephew, when I consider the sacred memory invoked with the Seder meal, I realize I don’t want to taste such bitterness, such unfathomable suffering. But if I do—and I somehow survive it—I hope I have the guts of the Jews never to forget.

In the early 1900s, Czech immigrants settled in the Klamath Basin in northern California. Along with their children and furniture and stories and songs and faith and hopes and, I bet, their tears, they brought their Czech horseradish root stock. The deep lakebed soil, abundant sunshine, crisp mountain air, and the colder winter climate allowed the stubborn horseradish plants to thrive. Just down the road from our family farm in Tulelake, California, off Highway 39, sits the old Tulelake Horseradish Company, founded in 1952 by a man named Burton Hoyle. By the 1960s this company’s thousand acres were producing nearly 40 percent of the horseradish sold in America. Hoyle called that Czech root stock “Tulelake No. 1.” The company that bought Hoyle out in 2001 moved production down to the Napa Valley. A Tulelake farmer named Scott Seus, whose family came from Eastern Germany, near the Czech border, still grows horseradish on his land. He’s one of only 20 horseradish growers that remain in the US.

My father grew up on a potato farm on Osborne Street, a significant stone’s throw from Seus’s farm. (“We don’t do potatoes,” Seus says. “And I’m not saying anything bad about potatoes. Potatoes is a pretty tough market. There’s farms that do it really well, and kudos to them for being survivors.”) My dad loved horseradish. He’d put it on his baked potatoes, mashed potatoes, scalloped potatoes, hash browned potatoes. He demurred when I asked to taste it once. I was only around five years old. “You’ll hate it,” he told me, as he took another bite of his potato, a dollop of horseradish carefully smeared on top. Tears—happy tears they seemed to me, for he was smiling—were streaming down his face. He couldn’t get enough of his Tulelake Old Fashioned Horseradish. It took me years—well after my father had died—before I would try it. I believe it blew a hole in my sinuses. I’ll never forget how painful it was. It made me cry. It made me miss my father.

FR. PATRICK HANNON, CSC, ’82, is an essayist. He teaches writing at University of Portland.

University of Portland

5000 N. Willamette Blvd.,

Portland, Oregon 97203-5798

503.943.8000

This website uses cookies to track information for analytics purposes. You can view the full University of Portland privacy policy for more information.